The disbarment trial of Trump’s attorney and constitutional legal scholar John Eastman resumed this past week on Thursday and Friday, and continues next on Tuesday, September 5. On Friday, Eastman’s attorney Randy Miller cross-examined the State Bar of California’s expert witness Matthew Seligman, an election fraud denier and attorney who serves as a fellow at the Constitutional Law Center at Stanford Law School, and former Secretary of State Elections Director Bo Dul also testified.

Tom Fitton, president of Judicial Watch, posted on X regarding the proceedings, “Kangaroo court proceedings in California to disbar John Eastman, one of the nation’s leading constitutional lawyers, for daring to provide legal advice on the Biden election controversy.”

Kangaroo court proceedings in California to disbar John Eastman, one of the nation's leading constitutional lawyers, for daring to provide legal advice on the Biden election controversy. https://t.co/edslH74uXz

— Tom Fitton (@TomFitton) August 26, 2023

Dul said on the stand that while serving as state elections director during the 2020 election, the only complaint of election problems she can recall the office receiving that she forwarded to the attorney general’s office to investigate was double voting. She worked at the progressive legal firm Perkins Coie before accepting an offer in 2019 to work under Katie Hobbs at the secretary of state’s office, and said she decided to take that position because “I believe in our democracy.”

After she left the secretary of state’s office, Dul went to work for the progressive organization States United Democracy Center. She said she sat on their Election Protection team working with government in Arizona. She is now serving as general counsel for Hobbs.

Dul spent much of her testimony declaring that the 2020 election in Arizona was conducted “securely” and “safely” and with “election integrity.” However, a couple of times when asked by Eastman’s counsel Randy Miller, she responded and said the election was conducted “freely and fairly.” She extensively discussed the “hand count audits” required by statute, which examine a very small portion of the ballots. When asked about the senate’s independent ballot audit of the 2020 election, Dul disparagingly referred to the “Cyber Ninjas’ quote-unquote audit.”

She dismissed the court challenges, “none of which produced any evidence that the results were inaccurate.”

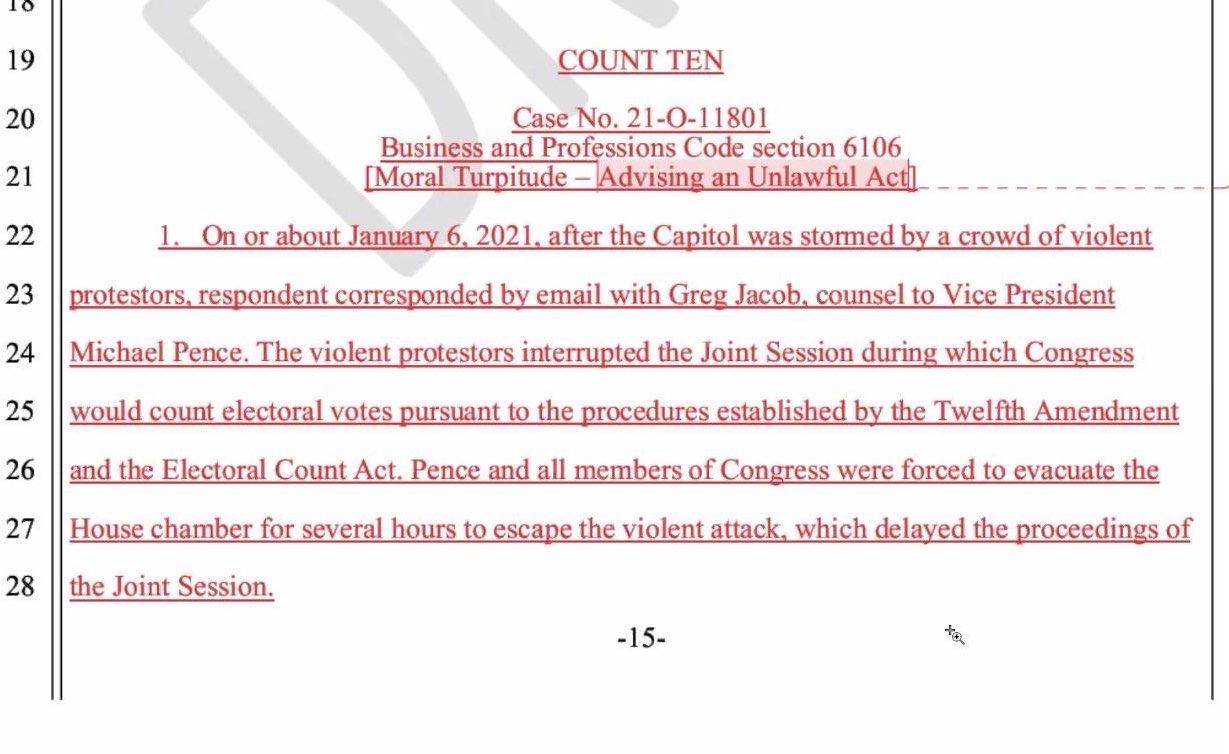

During his testimony, Seligman admitted that from 2019 to July 2023 he did not have an active license with the California bar to practice law. He said his license to practice law in Washington D.C. was also inactive some of that time, apparently due to being in a teaching position, but he did not recollect the dates. Seligman admitted he advised the California bar in 2022 on drafting the charges against Eastman. He said he reviewed the draft charges and recommended redline changes, including adding an entirely new count, “Moral Turpitude – Advising an Unlawful Act,” referring to J6, which he described in the count as “stormed by a crowd of violent protesters.”

Michael Cernovich, an attorney and political commentator in California, observed that although Seligman testified that he was finally placed on active status with the California bar in July, the bar’s website shows his status was actually reactivated on August 25, that day.

“I checked the official state bar website and he became active as of today,” Cernovich posted on X. “I wonder if the site will be altered now? This is actually a huge deal. If you’re not a lawyer it may not seem that way. It is. This is major. A legitimate scandal requiring review.” He included screenshots of the bar’s information regarding inactive status. Unauthorized practice of law is prohibited by the California bar’s rules.

I checked the official state bar website and he became active as of today.

I wonder if the site will be altered now?

This is actually a huge deal. If you’re not a lawyer it may not seem that way. It is.

This is major. A legitimate scandal requiring review. https://t.co/Blb4JD5yER

— Cernovich (@Cernovich) August 25, 2023

Miller asked Seligman about an email he’d sent to California bar attorney Duncan Carling, where he said he’d like both of them to coordinate and work with New York legal authorities in their efforts to disbar Trump attorney Kenneth Chesebro. Seligman is not licensed to practice law in New York.

Miller questioned Seligman about his testimony the previous day, where he’d claimed that there was no legal authority or precedent for the vice president to decline to accept electoral slates. He asked him about previous papers he’d written on contested presidential elections, including “Disputed Presidential Elections and the Collapse of Constitutional Norms” in 2018. The summary stated, “The Article provides a comprehensive account of the vulnerabilities in current law that leave the process susceptible to election subversion.”

One section was entitled “Fake Failed Election,” covering what happens when state legislators fail to choose a slate by the deadline. Seligman said there are some limited circumstances where Congress will get involved, although “it is not certain that a court would adopt that interpretation.”

Next, Miller asked Seligman about his use of the phrase “constitutional norms.” In his paper, Seligman wrote, “In each case, political actors playing constitutional hardball could execute the strategy while staying within the strict bounds of the law by abandoning informal constitutional norms. Drawing on historical data, it demonstrates that the losing party could have used one of these strategies to steal the presidency in 9 of the 34 elections since 1887 and the opposing party would have been powerless to stop the theft.”

Miller pressed Seligman about his writing on alternative slates of electors that did not have a certificate of ascertainment, meaning the state hadn’t certified them. Seligman referred to them as “putative electors” and did not say they were illegal.

Seligman discussed the legislative debates of 1880, where Republicans wanted the vice president to decide competing sets of electoral slates from some Southern states, but Democrats did not. There, a deal ultimately was reached by a special commission, allowing Republican Rutherford B. Hayes to become president and Democrat Samuel Tilden conceded.

Miller pressed Seligman about his qualifications, since Seligman didn’t appear to have studied election law until 2020 based on his testimony the previous day. Seligman insisted he had studied it for the past seven years. Miller asked Seligman if he knew how long Eastman had studied elections, and the judge stopped him from asking the question. Miller asked Seligman if he was aware of the scholarship of his colleague John Yoo, who is also a fellow at Stanford University with Seligman but disagrees with him about election fraud, and the judge shut down that questioning also.

Miller asked Seligman if his analysis contained any contemplation on whether the First Amendment applied to Eastman’s advice, and he said no. Miller asked whether Seligman was a registered Democrat and the judge interrupted him and refused to allow an answer.

At one point, the California bar’s attorney Duncan Carling objected to a question Miller asked Seligman and the judge sustained it. But when she was asked a few seconds later what she had sustained, she could not remember.

The trial is being livestreamed and may conclude the week of September 5 if not interrupted by the prosecution of Eastman in Georgia.

– – –

Rachel Alexander is a reporter at The Arizona Sun Times and The Star News Network. Follow Rachel on Twitter. Email tips to [email protected].

Photo “Bo Dul” by Arizona State University and image “John Eastman Trial” is by The California Bar Association.